Daniel Day-Lewis report from Gaza

Soldier on guard: "We have identified someone on two legs [code for human] 100 metres from the outpost.

Soldier in lookout: "A girl about 10." (By now, soldiers in the outpost are shooting at the girl.)

Soldier in lookout: "She is behind the trench, half a metre away, scared to death. The hits were right next to her, a centimetre away."

Captain R's signalman: "We shot at her, yes, she is apparently hit."

Captain R: "Roger, affirmative. She has just fallen. I and a few other soldiers are moving forward to confirm the kill."

Soldier at lookout: "Hold her down, hold her down. There's no need to kill her."

Captain R (later): "...We carried out the shooting and killed her... I confirmed the kill... [later]... Commanding officer here, anyone moving in the area, even a three-year-old kid, should be killed, over."

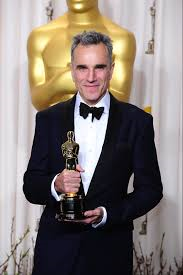

Authors in the Frontline: Daniel Day-Lewis

Inside scarred minds

March 20, 2005

On his first visit to the Gaza Strip, Daniel Day-Lewis meets the Palestinian families living in the heart of the danger zone and the psychologists who are counselling them

Mossa'ab, the interpreter, leads the way, carrying a white Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) flag. Its psychology team, myself and the photographer Tom Craig are in full view of an Israeli command post occupying the top floors of a large mill. It is draped in camouflage netting, as is the house close by. It is to this house that we are heading, across 200 yards of no man's land; the last house left standing in an area once teeming with life.

Mossa'ab, the interpreter, leads the way, carrying a white Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) flag. Its psychology team, myself and the photographer Tom Craig are in full view of an Israeli command post occupying the top floors of a large mill. It is draped in camouflage netting, as is the house close by. It is to this house that we are heading, across 200 yards of no man's land; the last house left standing in an area once teeming with life.

Civilians have been the main victims of the violence inflicted by both sides in the Middle East conflict. In the Gaza Strip the Israeli army reacts to stone-throwing with bullets. It responds to the suicide bombs and attacks of Palestinian militants by bulldozing houses and olive groves in the search for the perpetrators, to punish their families, and to set up buffer zones to protect Israeli settlements. It bars access to villages, and multiplies checkpoints, cutting Gaza's population off from the outside world. MSF's psychologists are trying to help Palestinian families cope with the stress of living within these confines; visiting them, treating severe trauma and listening to their stories. Their visits are the only sign sometimes that they have not been abandoned.

Israel's tanks and armour-plated bulldozers can come with no warning, often at night. The noise alone, to a people who have been forced to suffer these violations year after year, is enough to freeze the soul. Israeli snipers position themselves on rooftops. Householders are ordered to leave; they haven't even the time to collect pots and pans, papers and clothes before the bulldozers crush the unprotected buildings like dinosaurs trampling on eggs â€" sometimes first mashing one into another, then covering the remains with a scoop of earth. Those caught in the incursion zone will be fired on. Even those cowering inside their houses may be shot at or shelled through walls, windows and roofs. The white flag carried by humanitarian workers gives little protection; we'll have warning shots fired at us twice before the week is out.

Sometimes a family will not leave an area that is being cleared, believing if they do leave they will lose everything. It is a huge risk to remain. Sometimes a house is left standing, singled out for occupation by Israeli troops. The family is forced to remain as protection for the soldiers. Last year an average of 120 houses were demolished each month, leaving 1,207 homeless every month. In the past four years 28,483 Gazans have been forcibly evicted; over half of Gaza's usable land, mainly comprising citrus-fruit orchards, olive groves and strawberry beds, has been destroyed. Last year, 658 Palestinians were killed in the violence in Gaza, and dozens of Israelis. This ploughing under, house by house, orchard by orchard, reduces community to wasteland, strewn and embedded with a stunted crop of broken glass and nails, books, abandoned possessions. As we weave our way towards the home of Abu Saguer and his family " one of several families we will visit today "we are treading on shattered histories and aspirations.

Abu Saguer's own house is still standing, but its top floor and roof are occupied by Israeli soldiers. His granddaughter Mervat is with us, a sweet, shy seven-year-old with red metal-rimmed glasses, her hair in two neat braids held by flowery bands. She wears bright-red trousers and a denim jacket. Last April her mother heard an Israeli Jeep pull up briefly at the military-access road in front of their house. Some projectile was fired and when Mervat reappeared "she had been playing outside" she was crying and her face was covered in blood. They washed her. Her right eye was crushed. A month later in Gaza an artificial eye was fitted. It was very uncomfortable, so a special recommendation was needed from the Palestinian Ministry of Health to finance a trip to Egypt for one that fitted properly. Mervat needs this eye changed every six months, so the ministry must negotiate with Israel each time for permission to cross the border. Fifty cars are permitted to cross each day; each must carry seven people.

Abu Saguer has five sons and four daughters "You'll go broke with more than that," he says. He lives near the big checkpoint of Abu Houli in southern Gaza. He wants the photographer, Tom Craig, to take his picture and put it on every wall in England, Germany and Russia. He is 59. At 12 he went out to work, and at 16 he began to build the house he had dreamt of, "slowly, slowly" as a home and as a gathering place for his extended family. He had grown up in a house made of mud in Khan Yunis, which let the water in whenever it rained, and all his pride, hope and generosity of spirit had invested itself in this ambition. He had worked in Israel, like so many here, before the borders were closed to all men aged between 16 and 35.

For over 20 years, Abu Saguer had his own business, selling and transporting bamboo furniture. During the second Gulf war all his merchandise was stolen. After that he relied on his truck for income. He had cultivated 300 square metres of olive trees, pomegranates, palms, guavas and lemons in the fields around his home. After the start of the second intifada (Palestinian uprising) his crops were destroyed by the Israeli army "for "security". A road that services the Israeli settlements of Gush Katif had been built, and during our visit the traffic passes freely backwards and forwards, along the edge of the barren land where his orchards once flourished.

On October 15, 2000, Abu was at home with his wife when Israeli settlers emerged on a shooting spree. He and his family fled to Khan Yunis. After four days he returned. He was hungry. There was no bread, no flour. He killed four pigeons and prepared a fire on which to grill them. The soldiers arrived suddenly, about 20 of them, and entered the house. He followed them upstairs. "Where are you going?" he asked. One smashed his head into a door, breaking his nose. They kicked him down the stairs and out of his house. They kicked half his teeth out and left him with permanent damage to his spine. "If you open your mouth we'll shoot you," they said. They left, returning in a bigger group an hour later, to occupy the top of his house, sealing the stairway with a metal door and razor wire. The family has lived in constant fear ever since. The soldiers urinated and defecated into empty Coke bottles and sandbags, hurling them into his courtyard. They menaced his children with their weapons. After two years of this an officer asked: "Why are you still here?" "It's my house," he replied.

For four years, Abu Saguer has been afraid to go out, afraid to leave his wife and children alone. He is a prisoner in his own home, just as the Palestinians are prisoners within their own borders. The facade of self-government is an absurdity. The Strip, with its 1.48m Palestinians, is a vast internment camp, the borders of which shrink as more and more demolition takes place, and within which the population rises faster than anywhere else in the world. Meanwhile, about 7,000 Israeli settlers live in oases of privileged segregation. This is a state of apartheid. It's taken me less than a week to lose impartiality. In doing so, I may as well be throwing stones at tanks. For as MSF's president, Jean-Herv Bradol, has said, "The invitation to join one side or the other is accompanied by an obligation to collude with criminal forms of violence."

The late Lieutenant-General Rafael Eitan, the former chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), once likened the Palestinian p eople to "drugged cockroaches scurrying in a bottle". In 1980 he told his officers: "We have to do everything to make them so miserable they will leave." He opposed all attempts to afford them autonomy in the occupied territories. Twenty- five years on, it seems to me that his attitude and policy have been applied with great gusto. Every movement here in any of the so-called sensitive areas, which account for a large, ever-increasing proportion of the Strip (borders, settlements, checkpoints), is surveyed and reacted to by a system of watchtowers.

eople to "drugged cockroaches scurrying in a bottle". In 1980 he told his officers: "We have to do everything to make them so miserable they will leave." He opposed all attempts to afford them autonomy in the occupied territories. Twenty- five years on, it seems to me that his attitude and policy have been applied with great gusto. Every movement here in any of the so-called sensitive areas, which account for a large, ever-increasing proportion of the Strip (borders, settlements, checkpoints), is surveyed and reacted to by a system of watchtowers.

These sinister structures cast the shadows of malign authority across the land. On our third day, as we stood at the tattered edge of the refugee camp at Rafah, the forbidding borderland between Gaza and Egypt, bullets bit into the sand a yard and a half from where we stood. It was in this place " was it from the same watchtower? " that Iman el-Hams, a defenceless 13-year-old schoolgirl, had been shot just weeks before. She ran and tried to hide from the pitiless death that came for her. I felt her presence; the sky vibrating with the shallow, fluttering breath of her final terror.

I read this transcript before I left home; the cold facts ran through me like a virus. It is a radio communications exchange by the Israel Defense Forces, Gaza, October 2004. Four days later, crossing into Gaza, I'm still shivering: what the hell is this place we're going to?

Soldier on guard: "We have identified someone on two legs [code for human] 100 metres from the outpost.

Soldier in lookout: "A girl about 10." (By now, soldiers in the outpost are shooting at the girl.)

Soldier in lookout: "She is behind the trench, half a metre away, scared to death. The hits were right next to her, a centimetre away."

Captain R's signalman: "We shot at her, yes, she is apparently hit."

Captain R: "Roger, affirmative. She has just fallen. I and a few other soldiers are moving forward to confirm the kill."

Soldier at lookout: "Hold her down, hold her down. There's no need to kill her."

Captain R (later): "...We carried out the shooting and killed her... I confirmed the kill... [later]... Commanding officer here, anyone moving in the area, even a three-year-old kid, should be killed, over."

A military inquiry decided that the captain had "not acted unethically". He still faces criminal charges. Two soldiers who swore they saw him deliberately shoot her in the head, empty his gun's entire magazine into her inert body, now say they couldn't see if he deliberately aimed or not; another is sticking to his damning testimony.

This is the first section of an extensive report originally published in the Times by Daniel Day-Lewis. It is still available in its entirety here on www.politicsforum.org

See also short SPSC film The Killing of Iman Al Hams